|

|

|

|

This is probably the prettiest of Paris cemeteries, if only because - unlike Montmartre, Montparnasse and Père Lachaise - it is on a human scale. Tucked behind Saint-Germain-de-Charonne church, it has the look and feel of a village graveyard…and such it was until this area was absorbed by the encroaching city in the latter half of the 19th century. So remote and abandoned was this cemetery that the remains of a large group of Communards, killed by the Versaillais during the suppression of the Commune in May 1871, were uncovered only 30 years later, lying in a ditch.

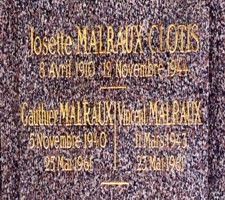

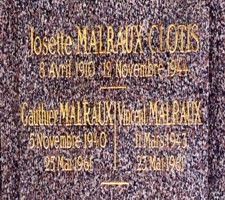

But only three of the 650 grave stones of Charonne are of interest to us. First off is that of André Malraux's mistress, Josette Malraux-Clotis, and of the two sons she bore him, Vincent and Gauthier. The three of them died tragically and the Great Impostor outlived them all. Josette died an excruciating death after her legs were crushed under a train in November 1944 while Malraux was away liberating Alsace (almost single-handedly, of course). Less than 17 years later, their two sons were killed in a car accident in Burgundy. A girl friend had just given the Alfa Romeo Giulietta to Vincent as a present. He drove, though he didn't have a driving licence.

At best, Malraux was an agnostic, but his two sons had been baptised and had at one time or another studied in private Catholic schools. Organising a funeral service for his offspring therefore did not pose Malraux too many existential problems. "On ne pouvait les enterrer come des sacs de pommes de terre", he explained.

Small ironies of history are close-by: just 20-30 metres away from the Malraux tomb, are the graves of two men who had been among André Malraux's mortal enemies: Robert Brasillach and Maurice Bardèche. Robert Brasillach was a relatively good poet, promising novelist and one of the first cinema historians (Histoire du cinéma, published in 1935, when Brasillach was 24). He was also editor of one of the most notorious collaborationist newspapers during the War, Je suis partout, in one issue of which he managed to write, "Il faut se séparer des Juifs en bloc et ne pas en garder de petits." But in his calmer moments, Brasillach was also capable of more elegiac kinds of discourse. Of the cemetery of Charonne he wrote: "(J'aime) cet endroit où l'on ne voit que les arbres, un clocher campagnard et d'où la ville énorme aux hautes bâtisses a disparu." Despite appeals for clemency from the likes of Colette, François Mauriac and Paul Valéry, Brasillach was executed by firing squad on February 6, 1945.

Facing Brasillach's grave, on the other side of the path that runs through the centre of the cemetery, is the grave of his brother-in-law, apologist and fellow Far Righter, Maurice Bardèche (see 5th arrondissement). When he died in 1998, Bardèche was remembered by Jean-Marie Le Pen as "a prophet of a European renaissance for which he had long hoped." In reality, one of the revisionist books, Nurembourg ou la terre promise has been banned from sale in France since 1952 because of its open sympathising with Nazi Germany. From 1952 to 1982, Bardèche was editor of a magazine called Les Sept Couleurs, one of the main platforms for Far Right ideologues throughout Europe in that period.

Return

to home page

Return

to home page  To

top of the page

To

top of the page